People often ask me two questions about Design Thinking. First, is the same as making, and second, do I like it. It’s obvious there are similarities and overlaps, and similar ways that they can be implemented well (or not so well). I think design is the key to modern STEM education, but it’s a mistake to think that using Design Thinking methodology is the same as teaching design. Design Thinking gets the “big D, big T” treatment because it’s a methodology invented at the Institute of Design at Stanford University (also known as the d.school) with assistance from ideo, a product design and consulting company.

Design Thinking, both in its origin and existing implementation in K-12 schools is grounded in product design and end user empathy. It’s a good thing to design with the user (or customer) in mind, but there are many more avenues of design than just making products that solve a problem for a specific audience. Many inventions were simply found by noticing unexpected results and following that path. Artists often say that the materials “speak” to them as they work. Authors say that their characters tell them how the story is going to unfold. In the same way, I think “making” values this kind of serendipity in the design process more than Design Thinking.

A search for solutions assumes that the problem is defined properly and we all agree on the values inherent in defining the problem — no small assumption. Basing everything on the “needs” of some group, audience, etc. is more about marketing than engineering, science, or art.

So, do I “like” Design Thinking? Sorta, maybe, kinda. I’ve seen nice things done in the name of Design Thinking, and I’ve seen too narrow, too constrained versions. It’s good in that I think empathy is a mindset that children should practice more often. But mainly, I distrust anything that’s been pre-packaged for K-12. Shrink-wrapping things kills them.

There are three things that schools should consider as they think about how and why to teach design.

- Learning. If you believe that constructionism is a valid explanation of how people learn, then you want a design process that allows people to build on their existing experience, make sharable, meaningful things, have time to assimilate new ideas and thoughts, and then iterate. This is a living, breathing process that includes and responds to the participants in real time.

- Teaching. What is the balance between telling and allowing exploration? Are the steps necessary and valid for all occasions? Who chooses the materials? Will the process or product be graded or ranked?

- The product. Does your process end with a real product or an imagined product? What is the balance between marketing and actual design? What are the values of your product?

I know there are thousand ways that schools implement Design Thinking so my thoughts here are an amalgam of what I’ve seen in conference presentations, websites, kits, and workshops for teachers and/or students. In many cases I’ve seen emphasis on teaching the steps, handouts that walk through every stage, and lots of post-it note driven group-think.

The focus on the steps and stages creates two problems:

- If you commit to an audience and plan, it’s an investment in a path that becomes more and more difficult to change as time goes on. If the materials you have don’t really support your idea, or you find unexpected obstacles, or even have a better idea, it’s too much of a penalty to change it up and follow that new path. It makes it worse if the stages are assessed and become part of a final grade. The success of many of the designs in a Design Thinking workshop is not a signal that it’s a good methodology, but rather that it’s too constrained.

- It fulfills the worst instincts of teachers to overplan and pre-digest any topic for their students. I’m sure it makes teachers feel better that they have a checklist and process to use back in their classrooms, but that’s a false sense of security.

Most things that people make for the first time don’t need a plan, storyboard, mindmap, outline, flowchart, diagram, etc. It’s false complexity to introduce those kinds of structures before they are really needed. If you make a wallet, make a wallet. Then and only then will you start to see how the materials work, what parts were easy and what was hard, that it might have been a good idea to make the outside a tiny bit bigger than the inside, etc. And then you must have time to do it again… and again…. A teacher trying to impose their favorite planning framework too early means that the student now has two tasks – to figure out what the heck the teacher wants in the bubble diagram, and also how to make a wallet.

Process is important, but so is the product. I’ve seen Design Thinking workshops that focus on imaginary products, probably for lack of time or proper materials. It’s great to have a vision of a trash can that floats around the ocean collecting trash, it’s another thing to make it work. Just making something float upright is pretty hard! But that’s how you really learn about floating (and leaking and density and absorbtion and making something work in the real world). I would classify designing imaginary products a bit like writing fiction — it’s a great literacy to have, but it’s barely design, and it’s certainly not engineering. Making things work is, to me, the most important part of design in the real world.

One more note about product – it’s not a given that just because a product solves a problem (as stated by one or more people) that this is a “good” product. What values come along with that decision? How is the design influenced by values – does it help or hurt the environment? Is it inclusive or only for some people? Does it make money at the expense of something or someone else?

Now, I’m not saying that “making” solves all these problems. The word has been handy — I can tell you there would be no “hacker movement” in schools. But the word is essentially meaningless. It’s what marketing people call an “empty vessel.” The art of marketing is all about searching for these kinds of words that people can fill with their own definitions. So everyone is happy but no one has to agree. I have no illusions that every time someone says “making” in education it’s automatically a wondrous experience of agency and enlightenment. Most of what I just wrote about the perils of Design Thinking I’ve seen unfold in exactly the same way in “maker” classrooms and workshops.

One final thing – I believe words matter. Of course thinking is good and making is good, and both together are even better. (Perhaps I should trademark “Design Thinkamakathon.”) However, the verbs “think” and “make” are very very different and signal the most important difference between the two. Thinking is internal, making is external. Thinking asks that an internal process happen in a certain way. It’s about intellectual behavior, which I think school already overemphasizes. It’s not wrong or useless by any means, just overdone territory.

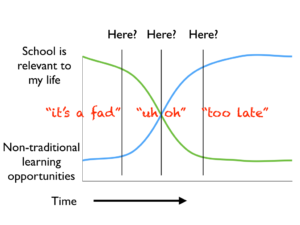

Making asks the maker to create something outside of themselves that expresses their own thoughts and ideas. I believe learning (and thinking) happens inside a person, but when you make something meaningful and shareable outside yourself, it cements that learning in place as a building block for the next iteration, which of course includes thinking. School has unfortunately paid little attention to the making part of the cycle, since it’s seen as messy and time consuming. Being clear that making real things that work is part of any real design experience is something I believe that schools need to think about, even if it falls outside the comfort zone.