When I talk about the maker movement in schools I do talk about tools and spaces, but I try to make the point that it’s about giving agency to kids in a system that most often considers students to be objects of change, rather than agents of change.

One of our reasons for writing the book Invent To Learn: Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom was to try to create momentum for the return of progressive principles of education, principles that have been yanked away from kids and teachers by politicians, corporations, and Silicon Valley gurus who think they know how to fix everything with an app.

I think this is a historic time, a second Industrial Revolution, where everything is coming together right at the right time. And like the Industrial Revolution, it will not be just a change in technology, but will resonate in politics, culture, economics, and how people live and work worldwide.

Politics, power, and empowerment

People may not think of the Maker Movement or making in the classroom as a political stance, but they both are.

Politics isn’t only about who gets elected, or the day to day “action” on Capitol Hill, it’s a negotiation of power in any relationship – who has it, who can use it, and over how many other people. The Maker Movement is about sharing ideas and access to solutions with the world, not for money or power, but to make the world a better place. It’s about trusting other people, often people you don’t know, to use these ideas for good.

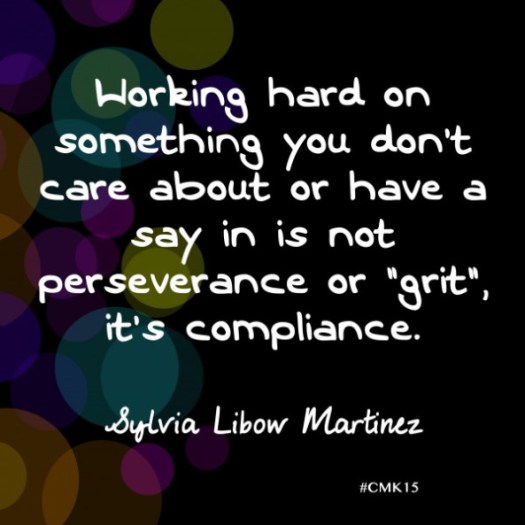

Making in the classroom is also about power and trust, and perhaps in an even more important way, because it’s about transferring power to a new generation. Young people who are the ones who will take over the world in the not too distant future. And if the learner has agency and responsibility over their own learning, they gain trust, not just the trust of the adults in the room, but trust in themselves as powerful problem-solvers and agents of change.

It is a political statement to work to empower people, just as it is a political statement to work to disempower people. That holds true for all people, not just young people. Being a helpless pawn in a game controlled by others is disempowering, whether you are a teacher, student, parent, or citizen of the world. Deciding that you trust another person enough to share power, or even more radical, give them agency over important decisions, is indeed political.

Making is not only a stance towards taking that power back, as individuals and as a community, but also trusting ourselves and each other to share that power to create, learn, grow, and solve problems. Empowering students is an act of showing trust by transferring power and agency to the learner. Helping young people learn how to handle the responsibility that goes along with this power is the sensible way to do it. Creating opportunities to develop student voice and inspiring them with modern tools and modern knowledge needed to solve real problems is part of this job.

And by the way, you can’t have empowered students without empowered teachers. Script-reading robot teachers will not empower students. We have to fight against the devaluation of teachers, and the devaluation of kids as cogs in some corporate education machine. We can do this, we can change minds, even if it’s hard, even if it seems impossible. We just have to do it anyway. That’s politics.

Education will change, how it changes is up to us

For education to change, it can’t just be tweaks to policy, or speeches, or buying the new new thing — teachers have to know how to empower learners every day in every classroom and be able to make it happen. Leadership is creating the conditions for this to happen.

Let me say it again – There is no chance of having empowered students without empowered teachers — competent, professional, caring teachers who have agency over their classroom and curriculum – who are supported by their leaders and community in that work.

So the question is – can the maker movement really have this kind of impact on schools? Or will this fade into a long line of fads and new-new things that promise educational revolution without actually requiring any change at all.

I see this as a singular time in history. There is an opportunity to leverage momentum swinging away from the testing idiocracy, away from techno-centric answers — to making education better with thoughtful, human answers.

Am I really saying that technology is the way to make education more human? Yes – but only if the technology is used to give agency to the learner, not the system.

I see a convergence of science and technology, along with the power of networks to connect people who are solving problems both global and local. I see people who are fed up with consumerism, opting out of corporate testing schemes – people who no longer have to wait for answers or hand outs from the government, from a big company, or from a university. They can figure it out, make it, and share it with the world.

Why is it different this time?

But haven’t there been a thousand “revolutions” that failed to change education? Why do I think this time is different? Why is this movement going to not be another failed attempt to “fix” education? Because my hero, Seymour Papert, the father of everything that’s good in educational technology, said so.

In his 1998 paper Technology in Schools: To Support the System or to Render it Obsolete, Papert said that the profound ideas of John Dewey didn’t fail, but were simply ahead of their time. Experiential learning is not just another school reform destined to failure because three reversals are taking place right now.

The first reversal is that children can be part of the change. Papert called it “kid power”.

Schools used to demand that students meet standards. But the time is coming when students will demand that schools live up to the standards of learning they have come to expect via their personal computers, even their phones. As Mimi Ito has written about so persuasively, more and more young people learn independently and follow their own passions via online sites and communities, and most of them are NOT run by traditional educational institutions.

The second reversal Papert identifies is that the computer offers “learner technology” instead of “teacher technology.” Many attempts at inserting technology into classrooms simply reinforce the role of teacher (video lectures, Khan Academy), replace the teacher (drill and practice apps, computerized testing), or provide management tools for the teacher (LMS, CMS).

But now we have affordable computers, sensors, and simple programming tools that are LEARNER materials. This transition, if we choose to make the transition, Papert says “…offers a fundamental reversal in relationships between participants in learning.”

The third reversal is that powerful ideas previously only available in abstraction, or in high level courses can now be made understandable for young children. Much like learning a foreign language in early years is easier, we can help students live and breathe complex topics with hands-on experiences.

I believe that this is overlooked in much talk about making in education. While I love the awesome “get it done” Macgyver attitude of the maker movement and the incorporation of artistic sensibilities like mindfulness – I think these are secondary effects. The maker movement is laying 21st century content out on a silver platter – things that we want kids to know, things kids are interested in, but are hard to teach with paper and pencil. Content and ideas that are the cornerstone of learning in the 21st century – from electronics and computer programming to mathematical and scientific concepts like feedback, 3D design, precision, and randomness – can be learned and understood by very young children as they work with computational technology.

But this third reversal may be the most difficult – these ideas were not taught to parents and teachers when they were children. Convincing parents and teachers that today’s children need to understand these new, fundamentally different concepts may be the hardest work of all.

No doubt, there is hard work to be done

The strategy for overcoming the last obstacle brings us back to politics and back to empowerment.

It means that for those of us who want to change education, the hard work is in our own minds, bringing ourselves to enter intellectual domains we never thought existed. Challenging conventions and cultural institutions that are ingrained in us in childhood. Sharing power with others, including students who might not do exactly what we expect them to do. Being willing to change everything, even when we feel we can change nothing.

The deepest problem for us is not technology, or teaching, or school bureaucracies – it’s the limits of our own thinking.

Politics is action, but everyone doesn’t have to be doing the same thing

What can we do when each one of us is in our own unique situation, each of us has a different position on the levers of power, and each of us sees with our own lens? Actually, I believe that this diversity offers strength, because no one person can do everything. Everyone has a part to play to take back the power of learning and create classrooms and other learning spaces where teachers and students are empowered and acknowledged as the center of the learning process.

And that, I believe, is ultimately a political act that will make the world a better place.

Several recent

Several recent