What’s in a name?

In the past decade, the terms makerspace, hackerspace, and fablab have come on the horizon. These are new names for what people have always done—come together to fix things, make new things, and learn from each other.

These spaces support learning and doing in a way that redefines both traditional schooling and traditional manufacturing. Smart tools, rapid prototyping, digital fabrication, and computational technology combine with the global reach of the internet to share ideas, solutions to problems, and best of all, the actual designs of things you can make yourself. These spaces are launch pads for a future where people of all ages can be agents of change rather than objects of change.

In Invent to Learn: Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, we use the term “makerspace” generically to describe these kinds of spaces, and also explain some of the history behind makerspaces, fablabs, and hackerspaces.

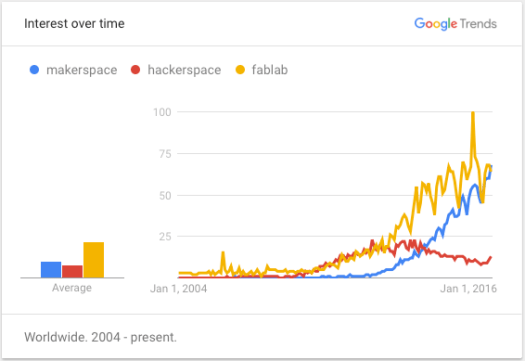

Here are some Google search trends on these terms:

What is…

- Hackerspace – “Hacking” is both the action and belief that systems should be open to all people to change and redistribute for the greater good and often done for fun and amazement. It’s unfortunately recently gained the connotation of illegal and invasive computer activity, which was not part of the original meaning. Hackerspaces are more prevalent in Europe than the US (and apparently Australia, see the map). A hackerspace is typically communally operated. There are many models and no common set of requirements. Hackerspaces.org has a wiki with over a thousand active spaces listed.

- Makerspace – Since MAKE magazine debuted in 2005, the word “making” has been adopted as a softer, safer alternative to hacking. This is especially true in K-12 schools, libraries, museums, and youth centers where the subversive aspect of “hacking” might be seen as negative or even criminal. You can see on the Google trends graph (above), that searches for the term “makerspace” started gaining momentum around 2013 as “hackerspace” started trending downward. “Makerspace” is now catching up with “fablab” (especially in the US). There is no single organizational body or rules about what a makerspace should be.

- Fablab – Short for “fabrication lab,” fablab is a generic term, a nod to Fab Labs (see next) without formally joining the network. Even though the “fab” refers to digital fabrication, the activities in fablabs aren’t restricted to 3D printing and laser cutting. They run the gamut of physical and digital construction, using tools, crafts, and modern technology.

- Fab Lab – The non-generic use of the term refers to spaces and organizations who participate in a network run by the Fab Foundation led by Neil Gershenfeld and Sherry Lassiter of the MIT Center for Bits and Atoms. Neil Gershenfeld is the author of the 2005 book “Fab: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop–from Personal Computers to Personal Fabrication” that predicted much of the impact that personal fabrication tools would have on the world. As of October 2016, the Fab Lab network includes 713 Fab Labs worldwide. All Fab Labs have a common charter and specific requirements for space and tools including digital fabrication tools, milling machines, cutters, CNC machines, etc. Every Fab Lab is required to have free and open access to the public and participate in the network.

- FabLearn Labs – Formerly known as Fablab@school, FabLearn is run out of the Transformative Learning Technologies Lab (TLTL), a research group led by Paulo Blikstein within Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education. These K-12 school-based labs, developed in collaboration with university partners internationally, put digital fabrication and other cutting-edge technology for design and construction into the hands of middle and high school students. The goal of FabLearn Labs is similar to the Fab Lab network, but with a focus on the special needs and practices that support K-12 education.

Other space names

- Tool sharing co-operatives, clubs, and community workshops – The are an infinite variety of non-profit and commercial organizations offering community tool sharing, classes, or incubation space for all ages. They usually offer different kinds of fee-based membership packages, but even commercial spaces may offer some free access in the spirit of serving the local community. These spaces offer different configurations of equipment, some focusing on heavy power tools, some offering artistic tools and space, while others are more electronics and computer-oriented. They also organize around different principles including community support, job training, DIY workspace, after-school/summer youth activities, small business incubators, recycling, or art studio. Some are adult only, while others have activities for youth and families.

- School – Don’t forget that there is a long tradition of hands-on learning spaces in schools variously called labs, studios, shops, libraries, and even classrooms! It doesn’t have to be a new space with a new name. Libraries don’t have to change their name to be a place where hands-on activities are as important as the books on the shelves. While a refresh is always good, a school makerspace should not mean throwing away books or closing the auto shop. There is incredible potential to be found in integrating these activities—and integrating the segregated populations they tend to serve.

- Libraries, museums, community centers and other local organizations are embracing the makerspace concept, with modern technology updates to hands-on activities and discovery centers beloved by generations of young people.

What’s the difference? What’s best?

As you can see, the differences are mostly historical, with increasing overlap in the terms. There are so many different models, with different missions, organization structures, and audiences, that it’s difficult to pin it down.

When these spaces serve children, the term “makerspace” is more prevalent than “hackerspace” simply because it sounds safe and legal. A few years ago, “fablab” was slightly more widespread globally, but I believe that “makerspace” has overtaken it in popularity. In any case, there is little difference between the generic use of fablab and makerspace. Makerspaces are now found in many K-12 schools, colleges/universities, libraries, museums, and community organizations. There is no special list of required tools, nor do makerspaces have to belong to any organization.

This looseness has pros and cons, of course.

Flexibility sets a low bar to entry

The benefit of a looser definition of makerspace is that it can be more inclusive and flexible. You don’t have to spend a lot of money or even have a special space. Anyone can have a makerspace; any place can be a makerspace. And as we claim in our book, Invent to Learn, every classroom should be a makerspace, where children make meaning, not just ingest facts to prepare for tests.

But while one makerspace may be a fully stocked industrial warehouse of cutting edge digital fabrication equipment, another is a box of craft materials, and others are everything in between. How do we even talk about, much less come to consensus about what works? How do we communicate best practices or any practices, for that matter? If everything and anything can be a makerspace, what is the value? What can we point to and say is special and different? We just don’t want to rename spaces and do nothing else. If “makerspace” comes to mean any space where kids touch something other than a pencil, then it means nothing.

Commonality provides context

One benefit of the formal Fab Lab model is that every space has similar tools. When they share information, plans, and processes, there is a better chance that it will make sense in other spaces. There is an expectation that every Fab Lab will participate in the network, learning and growing together while maintaining individual differences. This creates strong ties between spaces and a strong identity for the participants. There are events and opportunities for members like the Fab Lab conferences and Fab Lab Academy which offers credit and diplomas through nodes of the Fab Lab network worldwide. They can participate in global efforts like building sustainable wireless internet infrastructure, fabbing solar houses, and tracking global environmental data.

The FabLearn Labs have a similar model focused on K-12 makerspaces, with some requirements that create a cohesive network, but local flexibility for groups of schools such as the Denmark network.

Money required… for now

The downside of the Fab Lab requirements is that not every organization can afford the full list of tools. Since the Fab Lab charter requires open public access, they can’t charge membership fees. It’s a constant challenge to keep the doors open, the lights on, and to maintain staff and equipment. Some Fab Labs are associated with local universities, community organizations, or foundations that assist with the financial aspect, but others just get by. There is no doubt that money can be a limiting factor.

But this is just Fab Lab 1.0. The longer term vision, Fab Lab 2.0, is that a Fab Lab should be able to make a Fab Lab—but that is still in the future.

As with most things, there is no one right answer. Or rather, the right answer is the one that works for you and your community.

Networks, nodes, and identity

All of these space names imply similar ideas, and in fact, many spaces identify with multiple missions. You will find makerspaces listed on the Hackerspaces.org website and many Fab Labs that have close partnerships with K-12 schools. There are many spaces that create their own name in the spirit of their unique mission.

The first Fab Lab established off the MIT campus was the South End Technology Center in Boston. The center serves the community with low cost technology training, but also has innovative youth-led, youth-taught programs. The Youth Education Director at SETC is Susan Klimczak, who is also a Senior FabLearn Fellow and shares her expertise with educators around the world. This is just one example of how spaces can embrace multiple identities and belong to multiple networks to the benefit of all.

I don’t mind that there are many names for the spaces and experiences that people are having. It reflects the way people really learn, in unique and personal ways. There is no reason that every learning space, including the name, should not be unique and personal as well!

Learn more about making the most of your space – no matter the name in Invent To Learn: Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom.

Learn more about making the most of your space – no matter the name in Invent To Learn: Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom.

Let me help your organization make sense of making and makerspaces with creativity and innovation! – Sylvia Martinez